We’re not done with those sidewinder cattle barons, folks! Yep their still a burr in everyone’s backside kinda like Cookie! Aw, don’t get yer longjohns in a twist!

Now back to the real problem, and I’m not talkin’ about Cookie’s mulligan stew, today we’re talkin’ about the last big sheep raid in Wyoming, The Spring Creek Raid…

Cattlemen started driving large herds into the Big Horn Basin in the 1870s. Since they arrived first the cattlemen claimed prior rights to the grass on government lands for their herds to graze. However, the law stated otherwise giving sheepmen and cattlemen equal rights to the resources on public lands. Laws in the early 1900s made it a first come first serve situation and neither could claim rights over the grazing lands.

As discussed in the previous blogs on the Johnson County War and Tom Horn, the cattlemen of the late 1800s suffered from cattle glut on the grazing lands and targeted small ranchers driving them from their land by threat or by murder. Once things began to cool between the large and small cattle ranchers, all cattlemen turned their eyes toward a common enemy…the sheepmen.

The rising number of sheep on the range increased the pressure on the cattlemen. Sheep outnumbered cattle in Wyoming by the early 1890s. By 1894 there were 1.7 million sheep in Wyoming and 675,000 cattle. By 1909, there were more than six million sheep and only 675,000 cattle.

For those who don’t know, sheep consume the grass for miles. They eat down to the bare ground and when they leave a territory there isn’t any feed left for any other livestock. This makes it impossible for cattle to range with sheep. And at a time when the Wyoming range due to droughts, devastating winters and already over stocked ranges for cattlemen to watch thousands of sheep move onto open range divest it of all feed and move on was unthinkable.

The response, typical of the cattle barons, was to use violence to enforce their claims over the range. The cattlemen declared pieces of range off limits to sheep (the rule being “fence sheep in, fence cattle out). These men and their hired guns wreaked havoc upon the sheepherders and their property. For years a sheepherder would go missing, or be found shot on the range. A few men, like Tom Horn, would be tried and possibly convicted, but for the most part these murders and intimidations went unpunished and the sheepmen were left to their own defenses.

The cattlemen carried a chip on their shoulders and from their viewpoint were justified in the deprecations they inflicted on sheepmen and their wooly bands. One case, a sheepherder was taking a band (2,000 to 3,000 sheep) over the Big Horn range. He camped near the summit; a number of masked riders rode into camp about noon. The spokesman told the herder the altitude was entirely too high for his heart, and if he insisted on remaining up there it was sure quit on him, but if he would seek a much lower altitude, he might live to be an old man. The herder took the hint and beat a hasty retreat to the valley. After he left, abandoning his animals, the masked riders put the harness, a mother dog and her puppies in the wagon closed the door, tied the team of workhorses to the wagon wheels, poured kerosene over the wagon and set it on fire. They proceeded to shoot at least 50 sheep. Some had their eyes shot out, some with broken backs, legs shot off, some of their entrails hanging out. The men cut green Quaking Aspens clubs beat out the woolies brains.

The violence escalated and the sheepherders, determined to protect their herds and livelihood, formed the Wyoming Wool Growers Association in 1905. This Association would play an important role in prosecuting the men who carried out the Spring Creek Raid.

The last armed conflict between cattlemen and sheepmen occurred in the Nowood Valley at Spring Creek, seven miles southeast of Ten Sleep, Wyoming. The raid started in the spring of 1909, when two sheepmen, Joe Allemand and Joe Emge, along with three sheepherders drove 2,500 sheep from Worland, Wyoming east to Ten Sleep, about 25 miles. Allemand was a quiet man and admired by both cattleman and sheepmen of the area. An emigrant from France, Joe was an unassuming man married with three children. He had good credit and was a member of the Masonic Lodge. He kept his sheep on his own domain except in summer when he drove them to the mountain range.

Due to financial difficulties, Allemand sold a partnership to Joe Emge, a man not well-liked. A former cattleman, Emge, boasted he’d graze his sheep any place he liked and planned to run the cattlemen off the range.

On April 2, 1909, Allemand telephoned his wife from Ten Sleep telling her he would be home that evening. Listeners over the party line informed Emge’s enemies Allemand would not be in camp that night. Visitors to the camp from a nearby ranch disrupted Allemand’s plan when they stayed for supper. By the time they left Allemand determined it was too late to ride home. Allemand and his young nephew, Jules Lazier (a French subject) and Emge slept in the upper wagon. A young herder, sixteen-year-old Bounce Helmer and another Frenchman, Pete Cafferal, were in the lower wagon.

As darkness fell, seven raiders rode into camp. Two headed straight for the wagon, while five went after the sheep. The raiders fired shots and Helmer, fearing for his dogs, ran from the wagon. He was captured by the raiders along with Cafferal and both were tied up. Helmer recognized some of the men in the light of a lantern he’d lit.

No one emerged from the upper wagon and the raiders started firing into it. One man started a fire by throwing kerosene from Helmer’s lantern on the sagebrush under the sheepwagon. Allemand came out of the wagon and was shot down. The fire consumed Emge and Lazier before either could escape the wagon. When the raiders realized they’d killed Allemand, they fled. Helmer and Cafferal were able to free themselves and run to a neighbor’s for help.

When the Big Horn County sheriff, Felix Alston, reached the scene of the raid Joe Allemands body was lying near the smoldering embers of the sheep wagon a sheep dog’s puppy curled upon his chest. The charred bodies of Emge and Lazier were found nearby. The raiders left a trail of devastation. They killed dogs, sheep, and destroyed thousands of dollars of personal property. It was the deadliest sheep raid in Wyoming history.

Big Horn County used money forwarded by the Wool Growers Association to hire attorneys, cover the costs of trial and pay for essential actions such as concealing witnesses for their protection and for the protection of the case. Sheepmen contributed to the obtain the services of range detective, Joe LeFors, well known for his role in the conviction of Tom Horn, and therefore a man respected by the sheepmen of Wyoming.

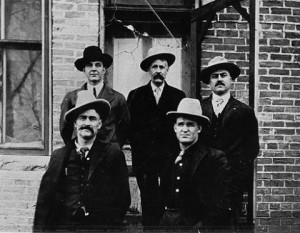

Unlike during the Johnson County War and previous actions against small cattlemen and sheepmen, officials were not going to turn a blind eye to this raid. Big Horn County officials began an aggressive investigation into the Spring Creek Raid and quickly established solid evidence against seven cattlemen, all charged with murder and arson. These men were: George Saban, Milton Alexander, Ed Eaton, Herb Brink, Tommy Dixon, Charles Ferris, and Albert “Bill” Keyes.

Charles Ferris and Bill Keyes turned state’s evidence. The remaining five, comprised of two ranchers, two cowboys and a former cowboy waited in the Big Horn County jail confident that the case against them wouldn’t even go to trial. These men knew the dismal Wyoming history for prosecuting sheep raiders, and the disastrous attempts to prosecute men engage in extralegal activities, such as the invaders during the Johnson County War, where the case never went to trial and the invaders received support from the governor himself.

And one of the men, George Saban, had personal experience with the often faulty Wyoming justice. As a participant in a July 1903 raid on the county jail which ended with two prisoners and deputy sheriff killed. The case against Saban and his colleagues collapsed under an atmosphere of intimidation.

A few cattlemen collected a large pool of money to fund the legal expenses of the defendants, and private lawyers were obtained to represent the raiders. Prominent politicians such as “Bear” George McClellan supported the raiders along with area newspapers. But things had changed in the Big Horn Basin by 1909, and all attempts to frighten witnesses, intimidate judicial authorities and frustrate jury selection failed.

One of the main reasons for this was a large new irrigation project that brought in farmers to the Big Horn Basin. As farmers, they had no particular sympathies for either cattleman or sheepman. Also, the governor of Wyoming was Bryant B. Brooks, a prominent sheepman, which probably added to his willingness to exercise state authority. He ordered the Wyoming militia to guard the streets of Basin City and keep citizens safe.

Contrary to the beliefs of the sheep raiders in November 1909 the trials did proceed. Herb Brink was the first brought to trial, and to the surprise of many there was little trouble in seating a jury. Farmers, with no stake either way, filled many of the seats, and the state militia kept order in the streets. The case was tried in the courtroom and not in the court of public opinion as many previous cases.

The state’s evidence provided by Albert “Bill” Keyes and Charles Ferris proved to be the most damaging as they spilled the whole story of the plan and the events the night of the raid including how Allemand staggered from the wagon and walked slowly away from it with his hands raised. Brink shot him dead, saying, “It’s a hell of a time of night to come out with your hands up.”

The State was well represented by the attorneys specially hired to assist the prosecution. Those lawyers included two from Sheridan, E. E. Enterline and William Metz, father of elected Big Horn County Attorney Percy Metz. The prosecution also included W.L. “Billy” Simpson, father of future Wyoming Governor Milward Simpson and grandfather of future Wyoming Senator Al Simpson. Billy Simpson had represented sheep raisers in various cases in the Big Horn Basin before 1909 and was therefore tainted in the minds of cattlemen. This was probably the reason he was not hired for the defense.

Eyewitnesses, including sheepherder Bounce Helmer, and three men who watched the raid from an adjacent house all testified. The raiders did not help their case by making the critical mistake of talking to their acquaintances. Billy Goodrich, whose testimony was secured by LeFors and who was the employer of two of the raiders, told the jury about a series of admissions made by Brink.

The jury convicted Brink of first-degree murder and sentenced him to hang. After this development, his fellow raiders stampeded to make separate deals with the prosecution. Brink’s death sentence was commuted, but five of the seven Spring Creek raiders were sentenced to serve prison terms. The two who testified for the prosecution were provided immunity.

The raiders’ fate was as follows: Eaton died in state custody. Saban escaped in 1913 and was never recaptured. Dixon was paroled in 1912. Brink and Alexander were paroled in 1914.

The convictions from the Spring Creek Raid put a stop to the havoc committed against Wyoming sheepmen. After 1909, there were only two minor raids in the entire state, and no one was injured in either. One of the prosecutors, Will Metz, summarized the meaning of the verdicts by saying, “It is significant of the beginning of a new era, of a period where lawlessness in any form will be no more tolerated [in Wyoming] than in the more densely settled communities of the east.”

And that folks is an example to all not to let the wool be pulled over yer eyes!

Don’t know about y’all but Cookie and me are amazed at how the same personalities, both good and bad, tend to keep showin’ up in all of these raids. Guess it’s true what they say about a bad penny! And doggonit if Cookie isn’t proof of that…Aw come on y’all saw that one comin’!

Now I’m off with ol’ Cookie, if’n he’ll let me on the same trail, into the sunset where we’ll be diggin’ up more Wyomin’ history! The good, the bad, and the ugly of it all!

See ya on the trail!!

SOURCES:

http://www.wyohistory.org/essays/spring-creek-raid

http://www.travel-to-wyoming.com/tensleep/spring_creek_raid.htm

https://sites.google.com/a/wyo.gov/the-spring-creek-raid-by-felix-alston/

It amazes me that such violence was allowed–and look at the dates–1909-1914! Far past the “Wild West” days. This was when we were suppose to have law as well as order. It’s that sense of entitlement that gets me. Great post. I had no idea just how violent Wyoming’s history was until I did research into the Johnson County Wars!

Hi, Anne,

I lived most of my life in Wyoming and never realized the extent of the violence there until I started researching for my books. As you mentioned, what is staggering about this raid is the dates well into the 20th Century. Also, as you mentioned the sense of entitlement and also the sense that they could conduct these raids and murder innocent people and get away with it.

Thanks so much for stopping by.

–Kirsten Lynn

That Was My Dad s Father My Dad Was Joe Allemand Jr