All right folks we’re back on the trail and headed north through ol’ Wyoming. We’ll be followin’ the deep ruts left by the wagons of those brave men and women who made this trek before us lookin’ for a better life. But ya know ol’ Cookie and me we zig and zag a bit, so ya just don’t know where we might end up before we get where we’re headin’.

“Cookie! Where the heck are we headin’?”

Guess we better stop off and load up on supplies…just in case. “Cookie pull this here rig into Fort Laramie. WHOOEEE look at those boys in blue!”

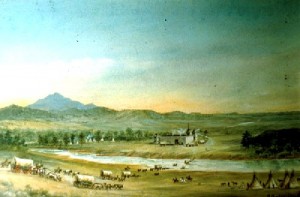

One of the most memorable shrines in Western America, and a location that appears in many books and movies about the West, is found in Eastern Wyoming at the junction of the Laramie and North Platte Rivers. Today the restored buildings of Fort Laramie remain preserved as a National Historic Site, where weary travelers can still stop by off the trail and step back in time.

One of the most memorable shrines in Western America, and a location that appears in many books and movies about the West, is found in Eastern Wyoming at the junction of the Laramie and North Platte Rivers. Today the restored buildings of Fort Laramie remain preserved as a National Historic Site, where weary travelers can still stop by off the trail and step back in time.

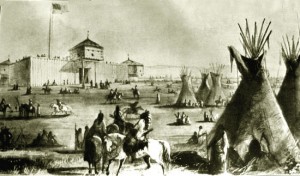

From 1834 to 1890, Fort Laramie served as a log stockade, adobe trading post, and evolving military post. Fort Laramie was a classic setting for the colorful pageant of the West. Explorers, trappers, traders, missionaries, emigrants, freighters, Pony Express riders, stage drivers, cowboys, homesteaders, as well as soldiers and Indians, all perceived Fort Laramie whether camp-ground, way-station, provision point, fortifications, or temporary home as an island of civilization where the Great Plains met the Rocky Mountains.

The reason for Fort Laramie’s importance was its strategic location on the great central continental migration, more commonly known as the Oregon Trail.

American and French-Canadian trappers were the first white men to explore the headwaters of the North Platte. The first documented visit to the Laramie Fork was seven men of the American Fur Company led by Robert Stuart. Stuart noted in his journal that here “a well wooded stream apparently of considerable magnitude came in from the South West.” He also referred to buffalo, antelope and wild horses in this region. Stuart’s party is credited with the discovery of a near-level Platte River route which led to a natural mountain gateway.

Several geographical names attest to the early infiltration here of French-Canadians, among them a shadowy figure commonly identified as Jacques Laramee, or Laramie. According to an 1831 report a J. Loremy, a free man, was killed by Arapahoe Indians in 1821 presumably near the river and later fort now bearing his name, the euphonious “Laramie” being bestowed on many features throughout Wyoming.

Throughout the 1820s fur trappers and other enterprising Americans such as, Jim Bridger, Jedediah Smith, and Thomas Fitzpatrick rediscovered the South Pass area, and lush beaver country west of the Continential Divide, and established a rendezvous on the Wind River.

In 1826, William Ashley of St. Louis sold out to Jed Smith, William Sublette and David Jackson, and Sublette brought the first wagon caravan up the Platte. In 1832, Sublette and Robert Campbell formed a trading partnership, contracting to supply others at the rendezvous, and in 1834, they built the first fort on the Laramie. The first fort Laramie was named Fort William (according to one of Sublette’s party William Anderson the name was in honor of the common name shared between himself and Sublette). In 1835, Sublette and Campbell sold Fort William to Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick and Milton Sublette. These men sold out within a year to the American Fur Company.

In 1826, William Ashley of St. Louis sold out to Jed Smith, William Sublette and David Jackson, and Sublette brought the first wagon caravan up the Platte. In 1832, Sublette and Robert Campbell formed a trading partnership, contracting to supply others at the rendezvous, and in 1834, they built the first fort on the Laramie. The first fort Laramie was named Fort William (according to one of Sublette’s party William Anderson the name was in honor of the common name shared between himself and Sublette). In 1835, Sublette and Campbell sold Fort William to Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick and Milton Sublette. These men sold out within a year to the American Fur Company.

In 1836, an overland caravan led by Thomas Fitzpatrick escorted the first white women to cross the continent, Narcissa Whitman and Elizabeth Spalding, missionary wives. These women enjoyed special consideration at the fort with chairs with “buffalo skin bottoms.” The women caused quite a sensation among the trappers and Indians.

In 1837, as Scotch nobleman, Sir William Drummond Stewart, traveled with artist Alfred Jacob Miller. Miller’s sketches remain the only pictorial record of Fort William. Later visitors of record include, Kit Carson, Joe Meek and Osborne Russell, Father De Smet, and Augustus Johann Sutter (whose ranch in Sacramento would later host its own hordes of gold seekers).

In 1837, as Scotch nobleman, Sir William Drummond Stewart, traveled with artist Alfred Jacob Miller. Miller’s sketches remain the only pictorial record of Fort William. Later visitors of record include, Kit Carson, Joe Meek and Osborne Russell, Father De Smet, and Augustus Johann Sutter (whose ranch in Sacramento would later host its own hordes of gold seekers).

Fort William enjoyed a monopoly of the trade in the North Platte until in 1841 when a new fort was built right under their noses. Fort Platte was an adobe-walled fort right on the bank of the North Platte and within rifle-shot of Fort William (or if you’re not measurin’ by shootin’ at your rival that’s about a mile apart).

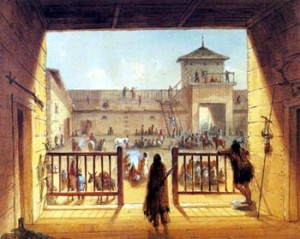

Not to be outdone the American Fur Company abandoned its log palisades and built a massive adobe structure. They named the new fort, Fort John honoring John B. Sarpy, an officer of the company. Fort John was used consistently in official correspondence, but as in the case of Fort William, the name Fort Laramie prevailed in popular usage.

For years the rivalry between the two posts intensified. Both sent trading parties to distant Indian tribes and flouted the illegal selling of liquor in the cut-throat competition. For a while both of these establishments thrived on the trade in buffalo robes, each spring sending them to St. Louis by wagon caravans or flat-boat flotillas down the Platte. Then in 1845, Fort Platte was abandoned leaving the field wide open for the American Fur Company.

Prior to 1841, the visitors to Fort Laramie consisted of trappers, traders, Plains Indians,  missionaries and the random adventurers. However, that was about to change with the arrival of the Bidwell-Bartleson expedition and the White-Hastings expedition the following year. These were the first avowed settlers bound for the west. Both of these expeditions hired Thomas Fitzpatrick, veteran mountain man, as a guide.

missionaries and the random adventurers. However, that was about to change with the arrival of the Bidwell-Bartleson expedition and the White-Hastings expedition the following year. These were the first avowed settlers bound for the west. Both of these expeditions hired Thomas Fitzpatrick, veteran mountain man, as a guide.

The year 1843 saw the first great migration to Oregon, about 1,000 people led by Marchus Whitman and Peter Burnett. These settlers crossed the Laramie and obtained supplies at the post.

The trickle to Oregon became a respectable river of 5,000 in 1845, and for twenty years after Fort Laramie witnessed the annual emigrant stream of humanity moving westward on prairie schooners. Camping, repairing equipment, buying provisions, and mingling at the fort became standard trail procedure.

While provisioning pioneers became a brisk business for the Fort, Indian trade continued to decline. Like a swift prairie wind brings a storm, conditions at the fort were ripe for change. The American Fur Company retired from the scene and a new owner better attuned to the rise of Manifest Destiny hailed its arrival with bugle and drum.

The Government had been looking at establishing a military post along the Oregon Trail, and the site of the Laramie Fork was recommended. President James Polk proposed the action and in May 1846 Congress approved “An Act to provide for raising a regiment of Mounted Riflemen, and for establishing military stations on the route to Oregon.” The first fort raised was Fort Kearney on the south bank of the Platte. But, in 1848, when the news of gold discovered in California raced across the country the urgency to extend the chain of forts increased.

Lieutentant Daniel P. Woodbury, Corps of Engineers, was authorized to purchase the buildings of Fort Laramie “should he deem it necessary to do so,” in 1849. On June 27, 1849, it was reported that this was the most eligible site and Woodbury purchased Fort Laramie from the American Fur Company for $4000.00. Major W.J. Sanderson of Company E, became the first commander of the fort. Sanderson reported that good timber, limestone, hay and dry wood were readily available and that the Laramie River furnished abundant good water for the command.

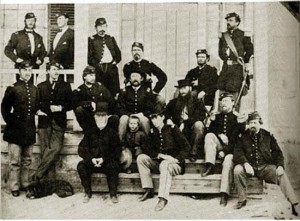

Company C, Mounted Rifles, arrived in July and Company G, Sixth Infantry in August completed the garrison. The temporary shelter of the adobe post was decrepit and infested with vermin. However, by winter a two-story block of officers’ quarters, a block of soldier quarters, a bakery, and two stables had been pushed to completion. This began Fort Laramie’s forty years as a frontier command post of the United States Army.

Company C, Mounted Rifles, arrived in July and Company G, Sixth Infantry in August completed the garrison. The temporary shelter of the adobe post was decrepit and infested with vermin. However, by winter a two-story block of officers’ quarters, a block of soldier quarters, a bakery, and two stables had been pushed to completion. This began Fort Laramie’s forty years as a frontier command post of the United States Army.

The Fort saw an estimated 30,000 Forty-Niners pass through on their way to California gold. This was but the first wave of covered wagon emigrants stampeding toward California. The following years, 1850-1854, saw even larger waves crashing against the little Army post on the Laramie, at times exceeding 50,000 each season.

To a large extent the history of the fort during this period is essentially its role in serving “this transient population during its Exodus from the States, across the vast wilderness known vaguely as Indian Territory to the Promised Land.” For many the Fort was the only civilized place between Fort Kearny and the West Coast.

The emigrant season of Fort Laramie was short, maximum of 45 days. One had to leave the Missouri jumping-off place no sooner than the spring rains could green the prairies for vital pasture for mules and oxen (any time during the last half of April) in order to reach the Sierra Nevadas well before October. Therefore the prime season for Fort Laramie was May-July with the majority of emigrants arriving in June.

The Fort provided care for wounded and sick, and sometimes the final resting place for travelers in the old fort cemetery. Some emigrants disposed of their surpluses here, others were in need of provisions, which the Post Quatermaster was able to supply, and the post blacksmith did a land-office business. However, the busiest place was the post sutler’s store where emigrant coin and valuables were exchanged for canned goods, liquor, patent medicines, lotions, muslin, sunbonnets, and other essentials.

The Fort provided care for wounded and sick, and sometimes the final resting place for travelers in the old fort cemetery. Some emigrants disposed of their surpluses here, others were in need of provisions, which the Post Quatermaster was able to supply, and the post blacksmith did a land-office business. However, the busiest place was the post sutler’s store where emigrant coin and valuables were exchanged for canned goods, liquor, patent medicines, lotions, muslin, sunbonnets, and other essentials.

Another busy functionary was the post adjutant, who ran the official emigrant register. Every wagon was stopped and numbers of men, oxen, horses, etc. were tallied. One such record for the season showed: “33,171 men, 803 women, 1, 094 children, 7,472 mules, 30, 616 oxen, 22, 742 horses, 8, 998 wagons, and 5,270 cows” recorded as of July 5,1850.

Contrary to beliefs both then and now, Plains Indians did not attack wagon trains as a habit, especially during the period of 1841-1858. However, two incidents would break the bonds of understanding and disrupt the peace on the Great Plains.

First in 1853, a North Platte ferryman, busy with emigrants, refused to transport a party of young Sioux. The Sioux seized the boat and one fired on the soldiers, who recaptured it. Lieutenant H.B. Fleming and 23 men were dispatched to the nearby village of Minniconjou Sioux to arrest the offender. The Sioux refused to give him up. In the ensuing exchange of gunfire three Indians were killed. The enraged Sioux then threatened the fort. Captain Richard Garnett, post commander, through skillful negotiations diffused the situation, but the seeds of mistrust were planted.

First in 1853, a North Platte ferryman, busy with emigrants, refused to transport a party of young Sioux. The Sioux seized the boat and one fired on the soldiers, who recaptured it. Lieutenant H.B. Fleming and 23 men were dispatched to the nearby village of Minniconjou Sioux to arrest the offender. The Sioux refused to give him up. In the ensuing exchange of gunfire three Indians were killed. The enraged Sioux then threatened the fort. Captain Richard Garnett, post commander, through skillful negotiations diffused the situation, but the seeds of mistrust were planted.

Then on August 18, 1854, eight miles east of the Fort a Mormon caravan passed a village of Brule Sioux. A cow wondered into the village and was promptly butchered by the hungry Indians. Upon complaint by the owner, Lieutenant John Grattan with an interpreter and 28 men was dispatched to arrest the offender. After a brief parley, a fusillade by the soldiers resulted in the death of Chief Conquering Bear, and the retaliatory massacre of Gratten and his entire command. Fort Laramie was threatened, but the Sioux moved away before inflicting any casualties there. But the harmony was destroyed and 25 years of warfare began.

The first serious disturbances did not occur until spring of 1862 when Sioux raided stations west of the fort, running off horses and scalping the tenders. To protect lines of communication vital to the Union Army fighting a Civil War, cavalry companies were ordered to the western theater. Colonel William Collins arrived at Fort Laramie with a battalion of the Eleventh Ohio Cavalry. It was his unenviable duty to guard the route between courthouse Rock and South Pass (a distance of over 500 miles). This blue line seemed powerless to intercept the mounted warriors of the Sioux, or to chase them down.

The first serious disturbances did not occur until spring of 1862 when Sioux raided stations west of the fort, running off horses and scalping the tenders. To protect lines of communication vital to the Union Army fighting a Civil War, cavalry companies were ordered to the western theater. Colonel William Collins arrived at Fort Laramie with a battalion of the Eleventh Ohio Cavalry. It was his unenviable duty to guard the route between courthouse Rock and South Pass (a distance of over 500 miles). This blue line seemed powerless to intercept the mounted warriors of the Sioux, or to chase them down.

In the spring and summer of 1864, there were large-scale Indian attacks on stations and ranches in Nebraska and Colorado, disrupting all travel. Then came the unauthorized surprise attack in November by volunteer troops under Colonel Chivington upon a Cheyenne-Arapahoe camp at Sand Creek near Fort Lyon in southeast Colorado. The massacre of around 250 men, women and children, far from squelching the Indian spirit, precipitated a powerful and vengeful alliance of tribes.

Sioux and Cheyenne focused their wrath on the key trail junction Julesburg, where they sacked the town and killed about 20 soldiers and civilians. Then they moved northward. Colonel Collins assembled a force from Fort Laramie to assist Mud Springs. They successfully protected the town and the warriors withdrew to the Powder River.

With the end of the Civil War plans were made to restore order to the Plains. However, the vastness of the desolate terrain, Indian aggressiveness, skill and agility, and poor initial organization and execution resulted in much success for the Plains Indians during 1865 and a dismal year for the soldiers of Fort Laramie.

Instead of a campaign to crush the tribes, in 1866, with Fort Laramie as the setting, runners were sent out from the Fort to “hostile” camps with invitations to a great council to be held in June. Hope appeared on the horizon, when Spotted Tail, head chief of the Brules, brought in the body of his daughter for burial among the whites because it was her express wish. In a ceremony containing all the pageantry of the military and the tradition of the Sioux her body was placed in a coffin on a raised platform on the plateau beyond the fort cemetery.

Peace commissioners assembled on 1 June with the chiefs of the Sioux and Cheyenne.  While the ceremonies were still in progress, Colonel Henry Carrington arrived with 2,000 troops, heavily armed and equipped to set up a chain of posts along the Bozeman Trail. To Red Cloud, such an armed occupation made a mockery of any peace treaty. He withdrew in anger, and the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1866 was the shortest lived peace treaty on record.

While the ceremonies were still in progress, Colonel Henry Carrington arrived with 2,000 troops, heavily armed and equipped to set up a chain of posts along the Bozeman Trail. To Red Cloud, such an armed occupation made a mockery of any peace treaty. He withdrew in anger, and the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1866 was the shortest lived peace treaty on record.

As forts were erected on the Bozeman Trail hostility continued to mount until in 1868 the Army and Sioux met again at Fort Laramie. The Forts on the Bozeman Trail evacuated and the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 gave the Sioux as a reservation all of present day South Dakota west of the Missouri River. It also gave them hunting rights in the great expanse north of the North Platte and east of the Big Horn Mountains. As mentioned in the post about the Battle of the Little Big Horn, this treaty failed, as well as leading to a series of small skirmishes and the massive clash in southeastern Montana. Though a temporary victory for the Sioux and Cheyenne, in the end the Government was left with the ability to dictate the formal relinquishment of the Black Hills.

Before the organized large-scale fighting against the Sioux and Cheyenne reached its climax there began an upsurge of civilian activity vitally affecting Fort Laramie. This was the mass influx of settlers to the Black Hills and the development of commercial traffic to and from Cheyenne.

Fort Laramie’s destiny was welded to the “Magic City of the Plains” about 100 miles to the south that began as a huddle of shacks springing up at the end of track when the Union Pacific construction crews reached that point in 1867. The Sioux wars and the stampeded to south Dakota combined to make Cheyenne a great supply depot and jumping- off place for the Black Hills while Fort Laramie became its principal gateway and guardian.

Fort Laramie’s destiny was welded to the “Magic City of the Plains” about 100 miles to the south that began as a huddle of shacks springing up at the end of track when the Union Pacific construction crews reached that point in 1867. The Sioux wars and the stampeded to south Dakota combined to make Cheyenne a great supply depot and jumping- off place for the Black Hills while Fort Laramie became its principal gateway and guardian.

In November, 1875, the Wyoming territorial legislature authorized the survey and designation of a road from Cheyenne via Chugwater Creek and Fort Laramie to Custer City. By March 1876, the new line was in operation. Vehicles on the new Black Hills Road included bull-trains, buckboards, spring wagons, and anything else that would roll. However, the queen of the road and bright symbol of Fort Laramie’s new era was the colorful Concord stage. The vehicle could accommodate nine first-class passengers inside and equal number on the roof, plus up to 1500 pounds of cargo and luggage. The driver managed the six horses with reins and the crack of his long whip.

The run to Custer City was 180 miles, or 266 miles to Deadwood. The route from Cheyenne to Fort Laramie followed the Chugwater and Laramie Rivers where there was a series of road ranches. The stop just below the fort was Three Mile Ranch, just off the military reservation, which doubled as a place of “entertainment,” complete with assorted belles for off-duty soldiers. The Post Trader was permitted to build a log structure on the fort itself known as the Rustic Hotel.

What would our Westerns be without the colorful stage and its potential holdup, or colorful occupants? The fine art of highway robbery reached a new peak in their assaults on armored stagecoaches with strong-boxes of gold heading for Cheyenne. Fort Laramie cavalry patrols were frequently assigned to guard danger spots or track down criminals. Among incidents in the Fort Laramie neighborhood were several killings at the Three Mile Ranch, the lynching of horse thieves by masked men just north of the iron bridge, and stage hold-ups along the Laramie River.

Among the patrons of the Cheyenne-Deadwood Tail were Generals Sherman, Sheridan and Crook, Chiefs Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane. In fact,  Calamity is alleged to have played various roles in the saga of Fort Laramie, including stage driver, roustabout, and occupant of one of the boudoirs at the Three Mile Ranch. Buffalo Bill Cody was another celebrated visitor, as a scout for the Fifth Cavalry.

Calamity is alleged to have played various roles in the saga of Fort Laramie, including stage driver, roustabout, and occupant of one of the boudoirs at the Three Mile Ranch. Buffalo Bill Cody was another celebrated visitor, as a scout for the Fifth Cavalry.

By the 1880s the small post of 1849 had blossomed into a city unto itself. The Fort structural complex gradually evolved into a sprawling assemblage of adobe, stone, frame and lime-grout buildings, about 70 Army buildings and civilian appendages were identified in 1888, being the most recent or most durable of a total of over 180 buildings constructed between 1849 and 1885.

The Fort was a stabilizing influence on the Great Plains, resembling a county seat in a region shifting from wild frontier to the beginnings of a permanent settlement. Range cattle and cowboys were replacing buffalo and Indians. Mines and ranches became the nuclei of communities sinking roots into the land. Stage lines faded as railroads, trunk lines and branches advanced. But the precursor of such civilization was doomed by the very peace it provided.

During this decade except for occasional assistance to civil authorities in upholding law  and order, field exercises, maneuvers, and target practice, military activity was at low ebb, while grand balls, celebrations, dress parades, theatricals, picnics, and tree planting became the dominant preoccupations. This is not the stuff of which epic history is made. And the bright star of the plains was fading fast.

and order, field exercises, maneuvers, and target practice, military activity was at low ebb, while grand balls, celebrations, dress parades, theatricals, picnics, and tree planting became the dominant preoccupations. This is not the stuff of which epic history is made. And the bright star of the plains was fading fast.

The actual demise of Fort Laramie occurred from May 1889 to March 1890. Various units of the Seventh Infantry were transferred to Fort Logan, Colorado. A detachment from Fort Robinson stripped buildings of doors, windows, fixtures, and accessories and the buildings and furniture rejects were auctioned off. The War Department issued its final order transferring to the Secretary of the Interior the military reservation and the wood and timber reservation at Laramie Peak, “the same being no longer required for military purposes.” And like so many who served in the garrison or passed through on the search for a better life the great military post faded into history.

But put those handkerchiefs away folks and dry those pretty little eyes, cause y’all can still make an Old West pit stop, just like our predecessors, at Fort Laramie! Why there’s still barracks and officers’ quarters ya can walk through or traipse across the parade grounds just like ya wore Blue! And iffin’ ya visit in July or August why ya can really experience the thrill of sweatin’ under that big ol’ Wyomin’ sun it’ll take ya back for sure. Doggone, Cookie! Does a gal have ta beg for a sarsaparilla? My biscuits are burin’ for sure!

But put those handkerchiefs away folks and dry those pretty little eyes, cause y’all can still make an Old West pit stop, just like our predecessors, at Fort Laramie! Why there’s still barracks and officers’ quarters ya can walk through or traipse across the parade grounds just like ya wore Blue! And iffin’ ya visit in July or August why ya can really experience the thrill of sweatin’ under that big ol’ Wyomin’ sun it’ll take ya back for sure. Doggone, Cookie! Does a gal have ta beg for a sarsaparilla? My biscuits are burin’ for sure!

Have fun at Fort Laramie folks! See ya next week on the trail!!

SOURCES:

FORT LARAMIE NHS: PARK HISTORY. (March 2003) www.nps.gov/fola/history/part1-1.htm

www.historicwyoming.org (Fort Laramie)

McChristian, Douglas C. and Paul L. Hedren. Fort Laramie: Military Bastion of the High Plains (Frontier Military Series). The Arthur H. Clark Company. 2009.

Excellent post, Kirsten. I know I’ll be peeking back at it when I need some info! Thanks for the great site as well! xoxox

Thanks, Tanya! I’m so glad this information will be of use to you! And as always, thanks so much for your sweet words about the site, it means so much to me.

–Kirsten Lynn

What an amazing post. I think I remember 1960’s TV show called Laramie.

Hi Ella! Thanks so much! I hadn’t heard of the show Laramie, but I just looked it up and indeed there was a TV series by that name about the stagecoach, interesting.

–Kirsten Lynn

Wow Kirsten, That was a great post, thanks for all the great information. I totally love your “western” voice. I really enjoy stories about the Old West and look forward to your next blog.

Thanks so much, Debby! I’m glad you made it to the campfire today and found the information worth the trip, and enjoyed my voice (I try)! 🙂

Hope to see ya ’round the campfire again soon!

–Kirsten Lynn

Kirsten, this site is fast becoming a favorite of mine for historical info. I am in the mental planning stages for my next book, and one line in this post has my head spinning for something that was a “hangup” for the story. Thanks to your post, I have a great new direction now. Thank you! (no, I’m not telling)

Awesome, Peggy! Your comment is such an inspiration, and if I can help a fellow writer work through a hang up all the better. Although, I think the fellow author should share. 😉 Best of luck on the new direction! I know my research into Fort Laramie sent me on a few new paths myself.

–Kirsten Lynn

oh, I’ll share…in due time. It’s still all in my head at this point. no words down on paper yet. Gotta get through my current WIP first.

Well, I’m glad you found inspiration ’round the campfire. Cookie’s coffee will do that for a person. 😉

Great post, Kirsten. There’s a ton of information here, but what stood out to me was 25 years of warfare over a cow. It never ceases to amaze me how quickly things can escalate past the point of no return.

That amazed me, too, Ally. Really both incidents were just that, minor incidents, but it never seems to take much to light a fire does it? And as you mentioned the slaughter of one cow caused 25 years of destruction and death on both sides.

Thanks so much for stopping by today!

–Kirsten Lynn

What a wonderful post! I don’t understand people who don’t find our history interesting. Must be the ones who haven’t learned from it either. 🙂

Thanks so much, Sharla! I feel the same, we have such a great history in this country and so diverse there’s something for everyone. 🙂

–Kirsten Lynn