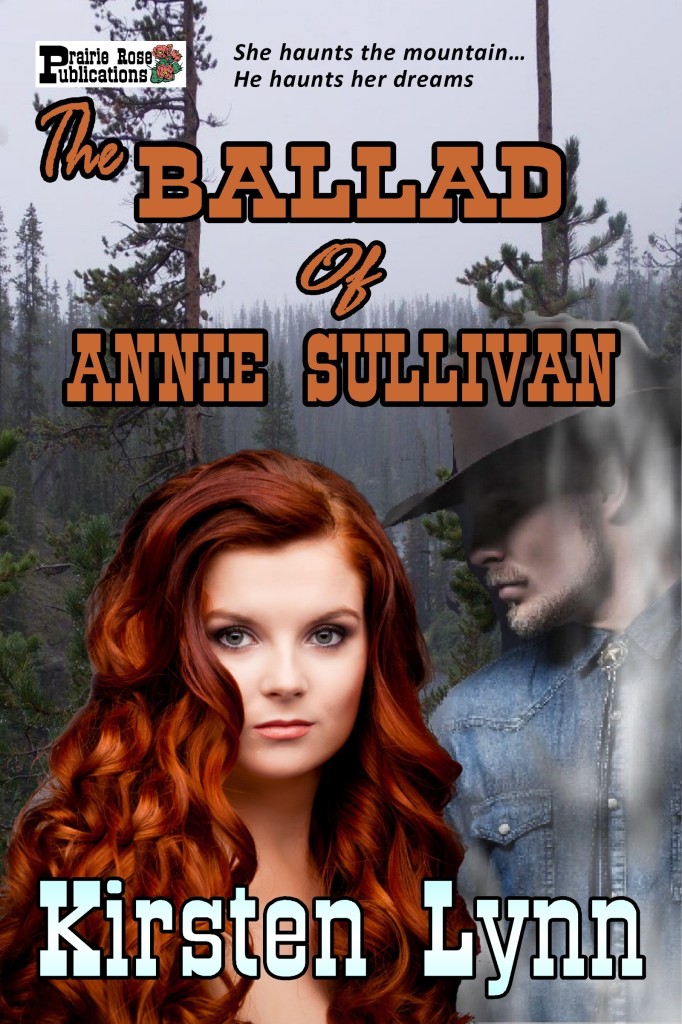

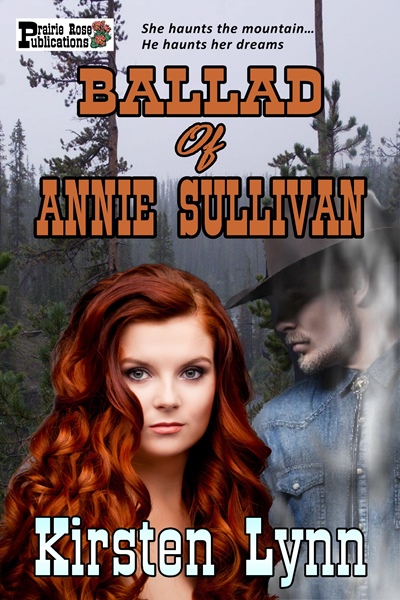

EXCERPT

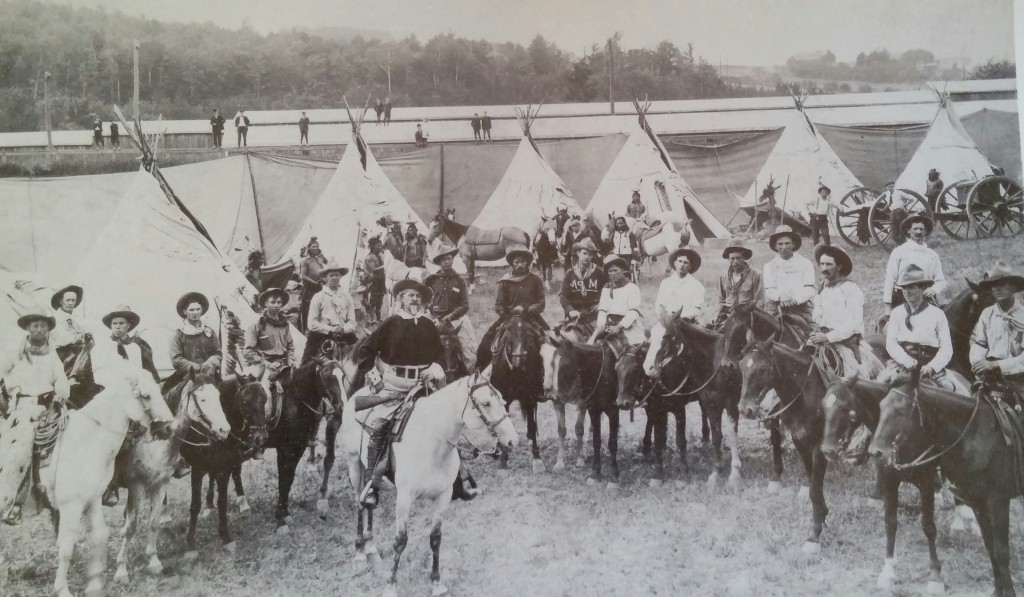

Little Creek Cow Camp, Bighorn Mountains, October, 1916

A slow shiver ran up Hank’s spine causing cold sweat to chill his neck and forehead. His gaze held tight to the spot where he saw the woman. She was real. She had to be real. He jerked his gaze down the rough, uneven terrain he climbed after jumping from his horse and tearing after a blur of red hair and blue dress. He closed in on his quarry until, in a thick copse of pine, she vanished quicker than a plate of his mother’s doughnuts.

Hank tugged up the collar on his wool plaid coat and tipped his hat down. Not even a damn track. He’d pawed the ground like a bull searching for tracks, but his efforts failed to reveal a toe print. He turned on his boot heel to run his gaze over the mountainside before he reached his mount. The buckskin gelding gave him the skunk eye, the brown gaze following Hank. His horse, questioning his sanity, itched Hank’s hide.

Stepping across leather, Hank settled into the saddle and patted the buckskin’s neck.

“Sorry there, boy. But didn’t you see her?”

Chap whinnied and shook his head.

Mrs. Baka, an elderly lady Hank helped out a bit who still held to a few of the gypsy ways of her people, once told him animals sensed spirits and things unseen by human eyes.

“Either you missed that special trait, boy, or I’ve been up here too long with only you and cattle for company.”

Hank reined Chap back to cow camp. The peace he usually found in these mountains eluded him as he made his way back to the small cabin serving as his summer home. The crunch of Chap’s hooves on dried leaves, pine needles and branches set his jaw to grinding as the noise he normally wouldn’t notice boomed inside him until he was sure his folks down in the valley heard them.

Since Cal and Josie Renner adopted him thirteen years ago, Hank volunteered to be the rider left on the mountain to secure the cattle and make sure the bulls scattered to breed those heifers ready. Every June like clockwork Hank, Cal, Josie and his brothers, except the littlest one at only five, gathered the herd and moved ’em up a narrow trail to cow camp on a grazing allotment the J Bar A shared with other ranches.

Then come September, Cal and the boys returned for the beef roundup. Pairs were separated from the yearling steers as ranchers worked together to earmark their beef. Hank breathed a bit better when they took the yearling steers down and headed for Parkman and he was alone again. He never begrudged his brothers and father the train ride to Omaha or Chicago to see the stock sold. As the only single Renner, Hank stayed put on the mountain while the others rotated which lucky couple got to head to the city—and which wife got a shopping trip and a few fancy dinners.

He glanced back. Thank the good Lord, the family would be back in two weeks to help take the rest of the herd down before the October fifteenth cutoff to be off the mountain. All this being alone was causing him to create red–headed women in blue dresses.

Aspen trees, dressed in gold leaves just a week ago, now stood bare and black against a sun fading into the west. Hank scrubbed a hand over his face and scratched the rough whiskers, more the start of a beard. How did a woman disappear quicker than summer in Wyoming? She was real. She had to be real.

Hank shook his head and released thoughts of the woman into the frigid air. Real or not, she was gone and he had cows to check. Accustomed to the routine, the buckskin made his way to the herd. The chill in the air drove the cattle to huddle together and Hank made quick work of counting the pairs. When he came up three short, he reined his mount toward the tree line where black shadows shifted between the white trunks.

He swung his gaze left and right. Even after confirming the shadows were his missing cows, he couldn’t unhook the feeling that eyes were on him. He’d felt eyes on him every summer, but had tossed it off to a rider from another ranch. This year, he couldn’t brush it off— because an alternative option had presented itself just an hour ago. Urging the three stragglers down to join their herd, Hank clicked his tongue and reined Chap toward a warm fire and some supper.

A mule rummaged around in the corral next to his sorrel. Hank rode past the holding traps and sent his eyes toward heaven. A groan rumbled from deep in his gut. Smoke curled from the stovepipe of the small cabin he and Cal had built the previous summer. For the first time, it didn’t invite him to settle in for the night with a belly full of beans and a good book. He no more than got Chap combed and oats, and fresh hay to the horses kept at camp, when a rough voice had his head ducking farther into the collar of his coat.

“Howdy, Hank boy. I took the liberty of gettin’ the beans on the fire.”

Hank wavered between being grateful the fire was already burning and irritation that he’d have to share it. He wasn’t much on people. Oh, he loved his family and missed them right now, but give him a couple of weeks down at the ranch and he’d be riding off alone first chance he got. About the only person he could stand longer than most was his twin, Jerry; but for being born a few minutes apart, they couldn’t be more different. Jerry was a man about town and never met a stranger; where, it seemed a person remained a stranger to Hank for years after they met.

His brothers all found girls the minute his stepmother Josie married Cal Renner, and Cal saw to it the family went to socials and the boys all went to school. Like dominos, each brother married—with the youngest, Mitch, being the first to marry. Each brother built a home on the ranch, and the brothers and their wives started having children almost as soon as the roof was put on the house.

Hank chose to go to the university in Laramie. After earning his degree, Hank wandered a bit, always finding his way back to the J Bar A. Two years ago, he planned to follow a family friend, Will Connor, to Europe and help the Brits fight against the Kaiser, but his Ma had raised the roof—so Hank stayed, but spent his time away from town and the busybodies asking why he wasn’t married and starting his family. His family respected his need to be alone. People like Walter Sorenson did not.

“Are ya comin’ in, or starin’ at the sky ’til it turns blue again?”

Hank kicked at the dirt, then started toward cabin. “What brings you up this far, Walter?”

“A little huntin’. And checkin’ on the ol’ place.”

Hank gave a nod. He ducked a bit to get through the door without knocking his head off. How two men well over six feet could build a place and not make the door passable for anyone over five foot ten, Hank couldn’t say. Could have been the few nips they had of the French wine Will Connor sent while they were measuring. Cal tried to tell Josie they’d been celebrating hearing from Will after a year of nothing when she found them propping up a wall singing God Save the King and toasting George V.

His mouth twitched with the memory as he toed off his boots and hooked his hat and coat on the wooden pegs by the door. The humor turned to a scowl at Walter’s hat and coat taking up room. He stomped over to the fireplace and sat on his heels, rubbed his hands together in an attempt to shake the cold and his sour attitude. The gas light over the table hissed, casting a dim light over the room. The Little Creek cow camp’s abode wasn’t a mansion, but it was spacious compared to most. Though one room, a kitchen area occupied one corner, complete with a Monarch iron stove and icebox, and even a few cupboards above the sink with a pump, so when Josie was there she didn’t have to haul water.

Memories warmed Hank and thawed his mind. He’d never call Walt a friend, but he couldn’t slot him as an enemy, either. It wouldn’t hurt him to be hospitable. Once he gained his manners, he unfolded to his full height. Walter stood dishing up beans from the Monarch stove onto an enamelware plate.

“You know most people up in these mountains?”

Walter flopped on the cedar bench, taking up one side of the table and swallowed a spoonful of beans. His dark eyes sparked with flames from the fire and curiosity.

“Not many left up here. Why?”

“Any have a daughter, or maybe a younger woman?”

Hank couldn’t say why he thought it was a young woman other than the fact she moved with the speed and grace of a deer. If truth be told, at twenty–eight he might not be as spry as he used to be, but he sure as hell didn’t want to hear a woman of eighty outran and outfoxed him.

If he hadn’t been staring holes into him, Hank would have missed the way Walter shifted in his chair and raked his fingers through what little was left of his gray hair. After a deep draw of coffee, the man wore a mask of innocence.

“A woman, ya say?”

“Yeah, you know…” Hank waved his hands drawing a curvaceous figure in the air, “a woman. Remember how they look?”

Walter’s eyes narrowed. “Vaguely. But there hasn’t been a woman up here in…” he swallowed hard; like emotion clogged his throat and smoke filled the eyes that just seconds before held fire. He pushed the plate away from him. “Ten years…ten years to the day next Sunday.”

Hank slid into the rickety ladder–back chair opposite Walter, his own hunger forgotten. Something rode him hard to find out about the woman who lived in the Bighorns. It was ten years ago, but something as intangible as air told him she held the key to the day’s insanity.

“What happened October 10, 1906?”

Walter’s eyes turned to black ice. “I’m not much on ghost stories, boy, so if you’re lookin’ for entertainment, look to someone else.”

Hank leaned back in his chair and could only stare at a man who lived to gossip, tell wild stories and entertain. Hell, even among the chatty hens of Sheridan, a man couldn’t find half the juice to a story as Walter Sorenson could give. And damn if what the man didn’t know, he could weave a wild tale around until a person didn’t care what was fact or fiction anymore.

Walter pushed off the bench and scraped the leftover beans into the pot before dumping his plate into a sink of soapy water. Hank watched the man shift his short stature from fire to water. He smoothed his mustache.

“I saw a woman today.”

A blue and white enamel mug hit the floor and Hank winced as the last mug was chipped. Then he turned his attention back to Walter. The man was white as the frosting on his brother Howard’s birthday cake. The buzz of the gas light hummed like a swarm of bees in the awkward silence.

“A woman?”

Hank shrugged, “Yeah, well at least from what I saw, which wasn’t more than a flash of red hair and her blue dress.”

“Annie,” the man choked out the name.

Hank hitched a brow. “Annie? You know her?”

A tremble shook Walt’s shoulders and his face darkened. “Used to.”

“Used to?”

“Annie Sullivan was raped and murdered ten years ago.”

Thanks for stopping by!!